The Profound Effect of AAMARP on the Art World and its Black Artists

In the late 1970s, the African American Master Artists-in-Residence Program (AAMARP) emerged as an innovative initiative designed to permanently change the landscape for Black artists in Boston and nationally.

Conceived by Dana C. Chandler Jr., AAMARP represented a pivotal shift in the art world. The program established the first long-term institutional residency for Black artists tied to creative productivity rather than short-term contracts.

It offered select Boston Black artists studio space indefinitely, provided they consistently worked on and exhibited their art. The program also adopted an “open studios” model, where artists were required to allow community members regular access to their spaces.

“This allowed community members, Black art lovers and aspiring Black artists to see how these exceptionally talented Black artists worked,” explains Chandler.

AAMARP launched with 13 artists in residence and featured an enormous gallery and community space. The gallery allowed artists in the program and around the world to exhibit their work in museum quality space. Visitors to AAMARP not only saw Black art but works by women, Latine, Native, and LGBTQ+ artists in often large exhibitions in an on-site gallery.

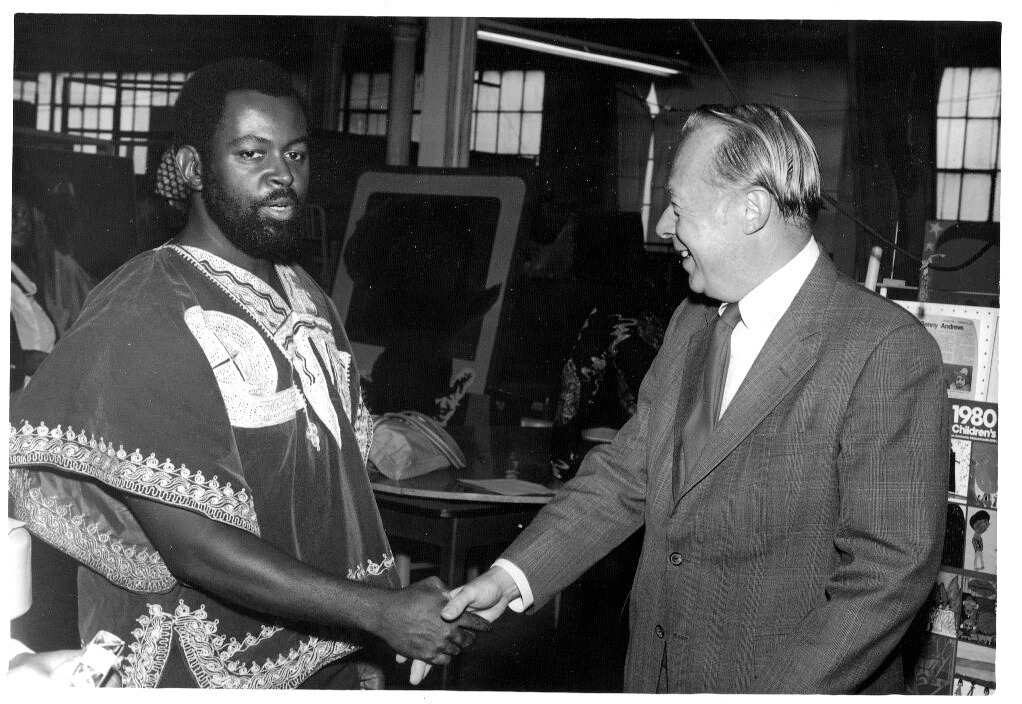

Supported extensively by Northeastern University, particularly then-president Kenneth Ryder, AAMARP became an influential model that not only transformed individual lives but also inspired systemic change across the art world.

The Vision Behind AAMARP

Chandler envisioned AAMARP as a revolutionary platform for addressing the chronic exclusion and marginalization Black artists faced. He intended to dismantle these barriers through institutional innovation and partnership with the university and community leaders.

He also knew AAMARP would solve a critical problem—the inability of many artists, especially Black ones, to securing stable and affordable studio spaces. That perpetual struggle significantly limited artists' creative potential and economic opportunities.

Ryder saw the young artist's vision and played an essential role in bringing it to life. His active support and commitment provided AAMARP with the institutional backing necessary to launch and sustain the transformative initiative.

His advocacy ensured that AAMARP could thrive during his tenure, reshaping the support structures available to Boston’s Black artistic community. It led to substantial support from the City of Boston and institutions across America.

As Chandler later explained, “I wasn’t only thinking of myself when I began planning AAMARP back in 1974. I wanted a space for African American artists to come and do the world-class art they're known for producing. I also wanted a space open to the Boston community, especially the Black community, since there weren't spaces for us.”

This dual vision—serving both artists and the broader community—was foundational to AAMARP’s identity and mission from its inception.

Chandler identified the future site of AAMARP while commuting through Boston’s Roxbury neighborhood. “I went past this building on the corner of Leon Street and Ruggles Street in Boston every day on the way to work at Simmons University,” he recalls.

“It was a large, old abandoned factory that I knew it would make great studio space for me.” This space, once a neglected factory, would soon become a haven for transformative Black art.

A Life-Changing Opportunity for Black Artists

AAMARP's unique promise—a practically permanent studio residency—set it apart. Artists could remain in their spaces and have art supplies paid for by the university as long as they consistently met program requirements.

This seminal model relieved artists from the relentless financial pressure typically associated with studio rentals and art supply purchases. This allowed them to invest their energies wholly in artistic creation and professional development.

The security and stability offered by AAMARP empowered artists to pursue ambitious creative visions without the looming threat of displacement. Artists were encouraged to experiment, innovate, and collaborate freely, significantly enriching their work. For many, this marked the first genuine opportunity to focus only on their art, profoundly transforming their personal and professional lives.

A Cultural Anchor for Boston's Black Neighborhoods

AAMARP’s physical location—situated across the street from Boston’s historically Black neighborhoods—offered vital geographic and cultural access to a community long excluded from formal art institutions.

Black Bostonians could easily visit the studios, connect with artists, and attend exhibitions and community events without the burden of navigating spaces that often felt restrictive or hostile.

This accessibility meant that the program didn’t just benefit individual artists. It became a cultural anchor in Boston’s Black neighborhoods. Families, educators, and youth groups regularly visited AAMARP, which served as both a safe space for visual and performing arts programming. By centering Black artists, AAMARP became a source of community pride.

As Chandler emphasized, “Its openness distinguished AAMARP from exclusionary art institutions that had long marginalized Black residents of Boston."

AAMARP’s Influence on the Wider Black Art World

AAMARP quickly became more than a local success story. It developed into a national model that redefined what institutional support for Black artists could look like. By demonstrating the effectiveness of stable, long-term residencies contingent only on artistic productivity, AAMARP set a new standard, inspiring many similar programs nationwide.

This pioneering approach not only challenged prevailing norms within the predominantly White art establishment, but also instigated critical conversations about racial equity and representation in the visual arts.

As more institutions and organizations adopted elements of AAMARP's structure, the entire Black arts ecosystem benefitted, fostering greater opportunities, increased visibility, and enhanced professional viability for countless Black artists.

AAMARP’s open-door ethos helped cultivate a new generation of young Black creatives who saw artists working in their own neighborhoods and understood that they, too, could belong in the art world. The program’s presence helped normalize Black artistic excellence and affirmed its place in the city’s cultural identity.

As Chandler recalled, “It also would be a community organization meeting and fundraising event space. It was a lecture venue and a spot for Northeastern and other college and grad school students to hold events and meet for class projects. School kids visited and made art.”

This multi-use vision extended AAMARP’s reach beyond the studio, embedding it within Boston’s educational and civic life.

Institutional Vision with Generational Impact

Decades after its founding, AAMARP’s legacy remains vividly present within both Boston's art scene and the broader art world. Some of its current artists, like Paul Goodnight, Reginald Jackson, and Susan Thompson, have been with the program since its early days. These artists careers bear testament to the power of equitable institutional support.

While it no longer has significant support from Northeastern University, the program continues to add newer artists.

The ripple effects of the program continue to inspire contemporary initiatives designed to provide sustainable platforms for artists traditionally sidelined by systemic biases.

Today, the influence of AAMARP is evident in numerous residency and fellowship programs across the nation, each echoing its original commitment to artistic freedom, stability, and racial equity. This enduring impact underscores how transformative institutional advocacy and support can be, profoundly affecting generations of artists and reshaping cultural narratives.

Even today, the cultural resonance of AAMARP in Boston’s Black neighborhoods is undeniable. Elders recall its early days with reverence, and younger artists continue to walk in the heritage it established. It wasn’t just a place to make art—it was a place where Black Bostonians saw their stories, struggles, and triumphs reflected and honored through creative work.

Protecting the Future of Black Artistic Institutions

AAMARP fundamentally altered the trajectory of many of Boston's Black artists and significantly influenced the national Black art landscape. By providing unprecedented stability and creative freedom, AAMARP showed the immense potential of institutional commitment to racial equity in the arts.

Ken Ryder’s pivotal role in championing and sustaining this vision at Northeastern University ensured that Chandler’s innovative concept became reality, setting a powerful precedent for subsequent generations.

Reflecting on AAMARP’s profound impact, it's clear continuing support for innovative initiatives is not just beneficial to artists and their communities. It's necessary in a time when Black-led institutions face erasure under the guise of austerity or neutrality.

These efforts must be intentionally funded, shielded from political attack, and expanded—not trimmed or tokenized. That's essential to preserve the cultural legacies and creative futures they protect.

Continued support for initiatives like AAMARP ensures not only the flourishing of Black artists but also the ongoing enrichment and diversification of America’s cultural and historical fabric.

© 2025. Dahna M. Chandler for ChandArts Media, LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this post may be reproduced, reposted, or used for AI/LLM training without the author’s express written permission.

Photo: Dana Chandler and Kenneth Ryder shake hands, a testament to Ryder's firm support of Chandler as a program founder and director and their genuine friendship.

Post a comment